](/img/posts/old-brick-wall.jpg)

Humans vs Cryptography, and why we'll never win!

Something happened to me recently which made me realise there is sometimes a fundamental disconnect between humans and cryptography, it’s often been said that humans are the weakest link, and in this post I hope to point out several ways that the very nature of being human hinders our ability do anything securely until the humanness is hammered out.

So, what happened is that I was working on a cryptographic protocol to create a secure communications session with another party, I had thought of seemingly everything: perfect forward secrecy, various degrees of anonymity, authentication of identity, ephemeral keys, active and passive interception etc.

And then I fucked up, really badly, in a way which meant that anybody could MITM the protocol, but up until that point I was absolutely sure I had accounted for everything, implemented the protocol correctly, tested my code and made it very clean and simple to understand.

The mistake was the coding equivalent of one team using centimeters and another using inches, a few single letter typoes introduced during refactoring and code cleaning resulted in a protocol which had passed my fairly rudamentary unit tests but ultimately failed to deliver one of the most crucial guarantees I was trying to achieve, and in turn opened my eyes to what it really means to verify and test cryptography and protocol guarantees.

At this point, I realised I am very much an amateur, maybe a skilled and knowledgable one, but nonetheless there was a fundamental gap in the way that I did things - and that is the fact that I’m human, and inevitably all humans fuckup at one point or another, often repeatedly and without knowing until afterwards.

Thankfully code can be fixed, lessons can be learned, forgiveness can be obtained and insight can be shared, hence this post :)

The Protocol

Originally it was designed to meet the following requirements:

- Use only the TweetNaCl or NaCl primitives

- Be very small and easy to implement in multiple languages

- Provide perfect forward secrecy guarantees

- Authenticate the identity of the Server

- Allow the Server to authenticate the identity of the Client if necessary

- Have a single round-trip handshake

Fairly straightforward, right? For the handshake all I needed to do was take a few of the cryptographic primitives, then with knowledge of their semantics and guarantees carefully devise a series of logical and symbolic operations which when followed resulted in both sides arriving at the same shared key which can then be used to transmit messages to each other using a separate transmission protocol.

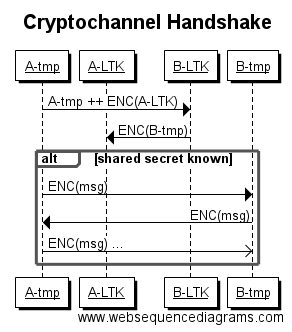

The handshake can be described using our friends Alice, Mallory and Bob, at the high level:

- Alice wants to connect to Bob

- Alice must know Bob’s Identity to ensure it’s really Bob and not Mallory

- If Bob cares about Alice’s Identity, likewise he must be able to verify it’s really Alice and not Mallory.

- When Mallory watches their communications, she must not be able to determine the real Identity of either party

- Mallory must not be able to intercept communcations and pretend to be either Alice or Bob.

- If Mallory steals the identity of either Alice, Bob or both, she must not be able to decipher past, present or future communcations just by watching - she must actively intercept a future handshake.

There are still problems with this scheme, especially what happens when the secret keys of one party are leaked, but for this specific use case this isn’t a problem that I needed to solve - for something like that I would instead refer to the Signal protocol and the work that Moxie Marlinspike and others have been doing to tackle these kinds of real-world scenarios.

Anyway, what is the Protocol and how does it work?

Firstly both Alice and Bob, where Alice is the Client and Bob is the Server, have long-term Identities; these Identities are Curve25519 key pairs.

These long-term Identities are only used once per session during the handshake to verify each other while negotiating a pair of session keys and a shared secret, to perform the handshake the Client must know the Identity of the Server, and the Server will be informed of the long-term Identity of the Client.

Handshake Round 1, Client to Server

- Alice creates an ephemeral key-pair for the session

- Alice creates a shared secret between her ephemeral Public key and Bob’s Public key

- Alice encrypts her long-term Public key with the shared secret, using a truncation of her ephemeral Public as the Nonce.

- Alice sends her ephermal public key, concatenated with her encrypted long-term public key, to Bob

Handshake Round 1.5, Server Processes Client

- Bob receives Alice’s ephemeral public key, and her encrypted long-term public key

- Bob creates a shared secret between his long-term Secret key and Alice’s ephemeral public key

- Using Alice’s truncated ephemeral public key as a Nonce, Bob decrypts her long-term public key

Handshake Round 2, Server to Client

- Now Bob knows Alice’s ephemeral and long-term public keys

- Bob generates an ephemeral key-pair for the session

- Bob creates a shared secret between his ephemeral secret key and Alice’s ephemeral public key, this is the shared secret for the Session

- Bob creates a shared secret between his long-term secret key and Alice’s long-term public key, this is the shared secret for the Handshake

- Bob encrypts his ephemeral public key with the shared secret for the Handshake (between his long-term secret and Alice’s long-term public)

- Bob replies with his encrypted ephemeral public key, prepended with a random Nonce

At this point Bob knows the session key, but Alice doesn’t yet have his ephemeral public key. In order for her to know what it is she must hold the private component of her long-term ephemeral key.

Sure, there are many more attributes that haven’t been explicitly stated, but it’s enough to infer the gist of it, the core principals of the protocol, and how it guarantees the requirements stated above.

Enough with Formalities, Where did I Fuck Up?

Essentially it was because of four letters, mistyped or switched around while writing and refactoring code. Sods law dictates that when something can be confused for another thing, it will be. For example you have long-term keys and short-term keys and abbreviate variable names to LTK and STK, this can introduce bugs if they get switched without breaking the tests.

And secondly because the tests didn’t verify cryptographic properties, only that the API could be used and generally does what is expected within reasonable bounds.

Take the following snippet for example, which uses their short-term key (which was sent in the same packet) to encrypt our short-term key in reply, by changing LTK to STK in a few instances the binding between the two long-term keys is broken:

- # Encrypt our STK with a secret between our LTK and their STK

- box = Box(self._my_ltk, self._their_stk)

+ # Encrypt our STK with a secret between our LTK and their LTK

+ box = Box(self._my_ltk, self._their_ltk)

...

- # Decrypt their STK with a secret key between their LTK and our STK

- box = Box(self._my_stk, self._their_ltk)

+ # Decrypt their STK with a secret key between my LTK and their LTK

+ box = Box(self._my_ltk, self._their_ltk)

While the protocol still worked at the API level, the underlying mechanisms that prevented a third-party from sitting in between of the two sides to intercept the handshake were broken, but the problem is clearer when you translate into a transaction between Alice and Bob:

- Alice knows Bob’s LTK

- Alice creates her STK, sends it to his LTK

- Bob creates his STK, sends it to her STK

A problem is introduced because Bob can’t verify that it was really Alice who requested the session - her first message could be interepted and a relay introduced because the reply from Bob is ignoring her LTK.

If Mallory intercepted Alice’s packet, and she knows Bob’s LTK, she could give Bob her own STK instead of Alice’s. Bob then creates his own short-term key and encrypts it with Mallory’s short-term key, which is intercepted and re-encrypted before transmission back to Alice.

If Bob sends his STK to Alice’s LTK then only the original sender of the message will be able to decrypt the response, and only the intended destination will be able to observe the long-term key to send a reply to. This scheme only works if one party knows the long-term identity of the other, which can choose if the other sides long-term key is needed.

Give me Solutions, not Problems!

If you want to make cryptographic claims you should probably provide a way of proving that claim, but even after research and formalisation you still have to implement it in a programming language, hit keys with your fingers, and pay attention to detail at the same time.

There are four fairly straightforward methods of avoiding these kinds of mistakes:

- Test your cryptographic guarantees

- Avoid potentially confusing names and language

- Make it as straightforward to understand as possible

- Seek peer review from knowledgable people

One of the downsides of these is that it takes more time overall for an algorithm or protocol to gain maturity, but by allowing time to pass and multiple fresh perspectives you are able to dedicate greater levels of attention to it in individual bursts.

To create a unit test for the problem above you would effectively have to create a copy of the bad code to verify that the fixed code isn’t compatible, or you would have to implement the MITM code, verify it works with the broken code and then ensure it doesn’t work with the fixed code. Is that worth it given the amount of time that has already been spent documenting and verifying code, which if carefully maintained is much more valuable than the problems its encountered.

Alternatively it might be worth investigating ProVerif and using that as a starting point, but there are always the additional steps of translating into another language and implementing it.

Anyway, now we have a solution, and more problems.

Source code available on GitHub